|

Tracing

Tale of Cemetery Park

Sunday, Sept. 24, 1989

By Elena Jarvis

Star-Free Press staff writer

Here is the chronological order of events that led to the creation of

Cemetery Memorial Park:

1862 - In response to Ventura's growth, a group of citizens go into

partnership to start the first city cemetery. The burial ground is divided

into four parts: The largest section, on land donated to San Buenaventura

Mission, for Catholics; one for Protestants; a Jewish graveyard; and

a final plot containing the bodies of Chinese, Indians and people of

other races.

1944 - Now full, the cemetery is abandoned.

1949 - The city erects a 10-foot high hedge to hide the decaying cemetery,

after plans to erect a park or housing tract over it are soundly rejected.

1959 - The State of California passes a law requiring graveyard owners

to set up an endowment, so that in the event of abandonment, money will

be available to maintain the grounds.

1963 - City fathers, led by City Manager Charles Reiman, put forth the

idea of making the cemetery into a park again, due to increased vandalism.

Despite some protests, the plan is approved.

Reiman obtains the consent of the Los Angeles Archdiocese and receives

the deed for the Catholic graveyard. By this time, the city already

owns the other portions.

1964 - Reiman sends letters to all the families of people buried in

the city cemetery that he can trace. Of 200 letters mailed to notify

people of the plan, 100 answers are received. Reiman says all replies

favor the change, as long as the bodies are not disturbed. But controversy

arises over removal of headstones because descendants say they were

not contacted.

Final removal of tombstones, granite grave markers and above-ground

crypts is completed in December and those buried in the mausoleum are

buried below ground. Tombstones and markers are transported to the Ventura

City Park Department yard on Hall Canyon Road, where families can pick

them up.

Archaeologist James Deetz of the University of California at Santa Barbara

and an assistant go to Hall Canyon Road and take photographs of some

of the tombstones for a book the archaeologist is writing on epitaphs.

1965 - At the end of the year, with little fanfare, the cemetery becomes

a scenic park. Families who request it can get a bronze plaque to mark

the site of their ancestor's grave. (City Clerk Barbara Kam fields several

of those requests every year.)

1972 - Unclaimed tombstones and granite markers - most of which were

not recovered by families - are ground up and used as fill for a levee

to protect the Olivas Park Golf Course, which is owned by the Parks

and Recreation Department.

HISTORY'S MARK

County pioneer's tombstone finds a resting place at his family's home

Sunday, Sept. 24, 1989

By Elena Jarvis

Star- Free Press staff writer

Quiet, serene and oddly uncrowded, Ventura's Memorial Park sits in the

center of the city like a big green, sore thumb.

Most Venturans have never heard of "Memorial Park," as it

is listed in the Thomas Guide map book. That's because locals have known

it as Cemetery Park since it was created in 1965 over the dead bodies

of 2,298 Ventura founders.

But the controversy surrounding the transformation refuses to die. Every

few years, the story comes back to haunt the Ventura Parks and Recreation

Department, which oversaw the project.

Those buried in the park include Maria Obiols, whose family's property

became one of the city's first subdivisions. There are the Argabrites,

a mother and two young children who lay side by side. Hobson, Ruiz,

Geniella, de la Guerra, Cardona and Clarck, all came to rest in the

old cemetery.

And there they remain, although the tombstones were removed and taken

to a storage yard on Hall Canyon Road run by the Parks and Recreation

Department.

For seven years the markers rested in the yard. Finally, in 1972, those

unclaimed by family descendants were ground up and used to fill a levee

at the Olivas Park Golf Course.

Over the years, the road to the east of the graveyard, Cemetery Lane,

became Aliso Lane. Cemetery Memorial Park somehow turned into plain

old Memorial Park on city maps.

What really rankles longtime residents is that the majority of the tombstones

were not claimed. When the removal project began, there were 100 replies.

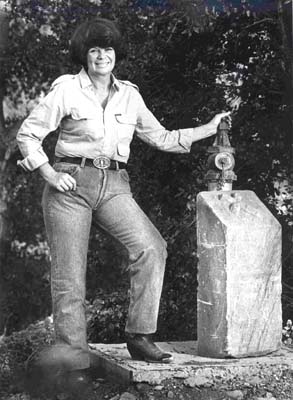

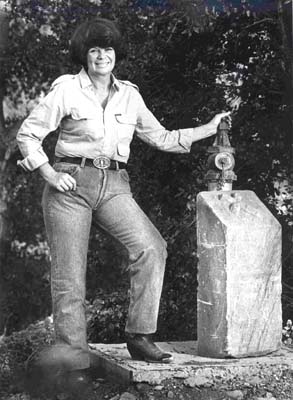

Pat Clark of Ojai is one of many who say their families were not notified.

The Clarks came to Ventura County in the 1800s. Among her relatives

are Robert Emmett "Whoopie" Clark, a three-term county sheriff

and U.S. Marshall for Southern California. Her cousin is William Clark Jr., the former California State Supreme Court Judge, who became President

Reagan's secretary of the interior. Her father, "Red" Clark,

was vice president of Shell Oil.

Even after 17 years, something happens every once in a while to put

Cemetery Park back on the map.

Two weeks ago, it was a surprise visit to Pat Clark at the Ventura County

Museum of History and Art, where she is editor of the quarterly magazine.

The spontaneous act of John Lashbrook of Ventura turned the sad saga

of the cemetery into a happy ending for Clark.

Lashbrook read about Clark in a March profile in the Star-Free Press

Vista section on Sunday. Her family history made him pause because 20

years before, his two teen-agers came home dragging a 400-pound tombstone.

"When John came to the museum, he introduced himself and said,

"I think I might have something that belongs to you," Clark

recalled.

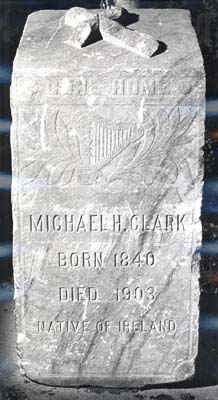

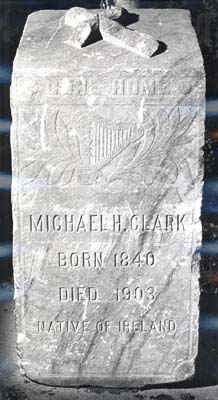

Lashbrook explained that the tombstone had a simple epitaph: "Gone

Home. Michael H. Clark, Born 1840, Died 1903. Native of Ireland."

Clark almost wept when she saw the Irish harp engraved on the tombstone.

She is a musician and her home is filled with Irish harps.

"My response was immediate because I had gone to City Hall and

I knew which family graves were in Cemetery Park. I knew there was a

large tombstone that belonged to my great-grandfather," said Clark.

As Lashbrook tells it, park workers used dump trucks and skip loaders

to move the huge monuments to the yard. The smallest weighed from 400

to 500 pounds. At first, tombstones were placed against a fence in alphabetical

order to help families locate them. When a neighbor complained about

the melancholy sight, the stones were laid flat on the ground. Eventually,

they became a giant jumble, victims once again of vandalisms.

In fact, the tombstones started a trend in the city - "grave making." The fad was to put stones in your front yard and set them up like real

graves, complete with mound and flowers.

One grave-maker quickly gave it up, saying, "I dreamed that an

old friend had died and came back to life. It was really bad. I never

dream so I thought it must have been caused by the idea of making the

grave so I went out and destroyed the plot."

The idea so outraged residents that City Manager Lee Horner issued an

official statement that the tombstones were private property. That was

in September 1972, the same year the tombstones were ground up.

"It was really a terrible thing that they did. They didn't notify

anybody," said Lashbrook, whose "nagging conscience led him to approach Clark at the museum.

"A couple of my kids went up to Hall Canyon and came back with the tombstone. Half of the high school kids went up there and dragged them out. Thank God Pat's great-grandfather's was on the top because if it had been in the bottom of those tombstones, it would have been there forever," he said.

Clark never met her great-grandfather, but being a historian knows quite a bit about him.

Before he immigrated to the United States in 1855, Michael Clark was a Fenian, a group that prededed the Irish Republican Army. Clark was a native of County Monaghan, on the war-torn border between the north of Ireland and the south of Ireland.

"He spent time in the Civil War and ended up in a Confederate prison camp. It was have been a dreadful experience. He was born in 1840; the worst year of the great famine of Ireland was 1847. Then to come to this country -- the land of hope and promise -- and to end up in a prisoner-of-war camp," Clark recounted.

"From what I've heard he was a very bright man, but an embittered person. He was an academic sort, but without any formal training. And he was a dreamer. Maybe that's why I identify with him," she said. "He wasn't much of a farmer. I've read old papers and he seemed to spend a lot of time looking for gold in the hills of Ojai. Which he never found, of course. His house, the house he built, is still standing next to the Ojai Lumber Company on Ojai Avenue."

Some people, Clark added, say they have seen a ghost at the house. But it's the ghost of a woman, not a man. To this day, a few Downtown Ventura residents swear they've seen the uneasy spirits of Cemetery Park floating around the neighborhood.

If one of those apparitions was Michael Clark, he should be at peace now.

"I'm planning to plant a big oak tree and I'm going to put the gravestone there. I also have an oak [oak grove Indian, actually] bowl that my great-grandfather, the same person, dug up in the upper Ojai. I want those two pieces under the tree," Clark said.

Pat Clark of Ojai stands by her great-grandfather's tombstone,

one of the few to survive from Cemetery Park in Ventura. She treasures

the tombstone, which has just been returned to her, for its family and

historic significance.

Michael

H. Clark died Feb. 3, 1903; his tombstone contains a carved Irish harp

and the words "Gone Home." |